Talking to Machines, Part 2: Crafting Clear Conversation with Prompt Engineering

Collaborate with AI using a prompting approach built from skills you already have

Talking to Machines is a three-part series exploring the rich changes in interacting with AI and what that means for improving how we work with it.

In this series, I’m looking into practical ways of bringing generative AI into our workflows from my perspective as a human-centered designer, and my experience leading product design for teams, products, portfolios, and global information systems.

Part 1 offered a conceptual anchor for where we are in AI’s evolution, a bird’s eye view of how LLMs work, and a foundation for us to explore prompt and context engineering in the next two parts.

If you haven’t read Part 1 yet, you may want to start here:

Here, Part 2 is organized into three sections: first, where prompting began. Second, what prompt engineering actually is and how to think about it with simple, accessible analogies. And third, a deeper dive into how to get better at prompting over time. It includes useful ways of thinking, some practical techniques, and where human-AI collaboration is headed.

Part 3 will delves into how we are designing the AI’s world through the growing field of context engineering.

Please subscribe to get future essays and support this work.

Or simply give this post a like :)

In the beginning

When prompting first appeared, the workflow was quite barebones:

Type your question

Press enter

Get a response

It was the same as typing into a search bar, just with a new kind of magic — instead of pulling up websites and connected information with a search powered by cross-linking and knowledge graphs, it was responding to us. Each word was now generated probabilistically on the fly by a trained Large Language Model (LLM) in the background. And better yet, we could continue the conversation.

We were witnessing the beginning of a future we had dreamed of and feared. Google, but something that talks to you. A chat app, but with a robot that has read all the things. Was it sentient? Some of us were hoping Isaac Asimov’s laws of robotics were already programmed in.

The tech spread like wildfire, with ChatGPT reaching an estimated 100 million monthly active users within just two months and becoming the fastest-growing consumer app ever. It was the first time you could truly type natural language into an input, press enter, get a natural language response, then keep going from there.

This was something knowledge management technology teams filled with brilliant data scientists and engineers had been trying to crack for years. Various mathematical approaches and compute demand had pushing the latest hardware to the edge of failure for years.

And at that point, we were all experimenting with the technology. Suddenly we could talk to this new free tool and we were all figuring out how to talk to it. We quickly discovered there were skills that, as a community of pioneer users, we would need to uncover.

Nobody quite understood how prompts shaped responses. The only way to set context and guide the conversation was through the prompt, yet it felt like a black box sitting right in the center. How could we better influence those next-word probabilities?

Tricks and techniques were passed around and evolved as the community attempted to wrangle the beast using the one tool available — the prompt. Prompts needed to be complex and comprehensive as everything had to be jammed in the input box. And in those early days, that box was interpreted by erratic LLMs in their infancy.

From that cowboy era of prompting emerged the craft of “prompt engineering”. And it’s come a long way since the early days. Thankfully as LLMs have evolved, so too have other tools for setting context alongside it, allowing the role prompting plays to get increasingly more specific than a catch-all.

In this Part 2 of the 3-part series Talking to Machines, we will define prompt engineering in simple terms, make it more tangible with person-to-person analogies, and explore some ways you might hone your conversations over time as it continues to evolve. The intention here is to ground newcomers in core concepts while surfacing perspectives and practices even experienced users can use to sharpen skills over time.

Later, in Part 3, we will expand our view of context-setting beyond prompting, into the growing field of context engineering. As this area expands, so does our ability to shape and refine how we collaborate with AI. We are leaving behind the ephemerality of one-off chats for a new world of connected conversations.

Basic prompting

Say no to bad meetings

Have you ever been invited to a team meeting with no agenda and a vague title? One where you were greeted with a “prompt” that you were all gathered simply because there were a lot of things to do?

These meetings run on a generally broken assumption that by getting together, good stuff will happen. We are all smart people in a room, therefore, progress will follow. It’s an exercise in extreme faith, marred by a lack of appreciation for the value of guidance and structure in good collaboration. A little intentionality goes a long way.

Chats with an LLM are similar, with you always playing facilitator. Unless you are in pure exploration and tinkering mode, coming in with an intent and skilled hands makes all the difference. It’s about anchoring the conversation with some frame of reference before diving in. Much of the time, the first part of a conversation with AI is focused on doing just that.

Remember, at the most rudimentary level, we are influencing next-word probabilities when talking to machines. And as with team work, context and structure are important as an anchor and guardrails, especially for more divergent modes of thinking.

In the AI practitioner community, there is a growing recognition that these skills are starting to standardize. Using AI is beginning to look much more managerial. As teams start consolidating into one person, the load of setting context and guiding progress is becoming more a basic part of knowledge work. It’s no longer reserved for the team leads managing projects and teams.

This shift brings pernicious societal risks that will need continuous unpacking by our community, which I briefly touched on in a recent post. That’s a deeper area that we should keep getting into another time. For this piece, we will stick to the in-the-moment skillset of talking to a machine — a.k.a. “prompting” — while setting up the stage to explore context engineering in Part 3.

What is prompt engineering?

Put simply, prompt engineering is the careful craft of shaping inputs so AI gives you accurate outputs that meet your needs.

It’s learning how to talk to machines intentionally. The skillset has been evolving since the advent of generative AI, becoming more specific and focused over time.

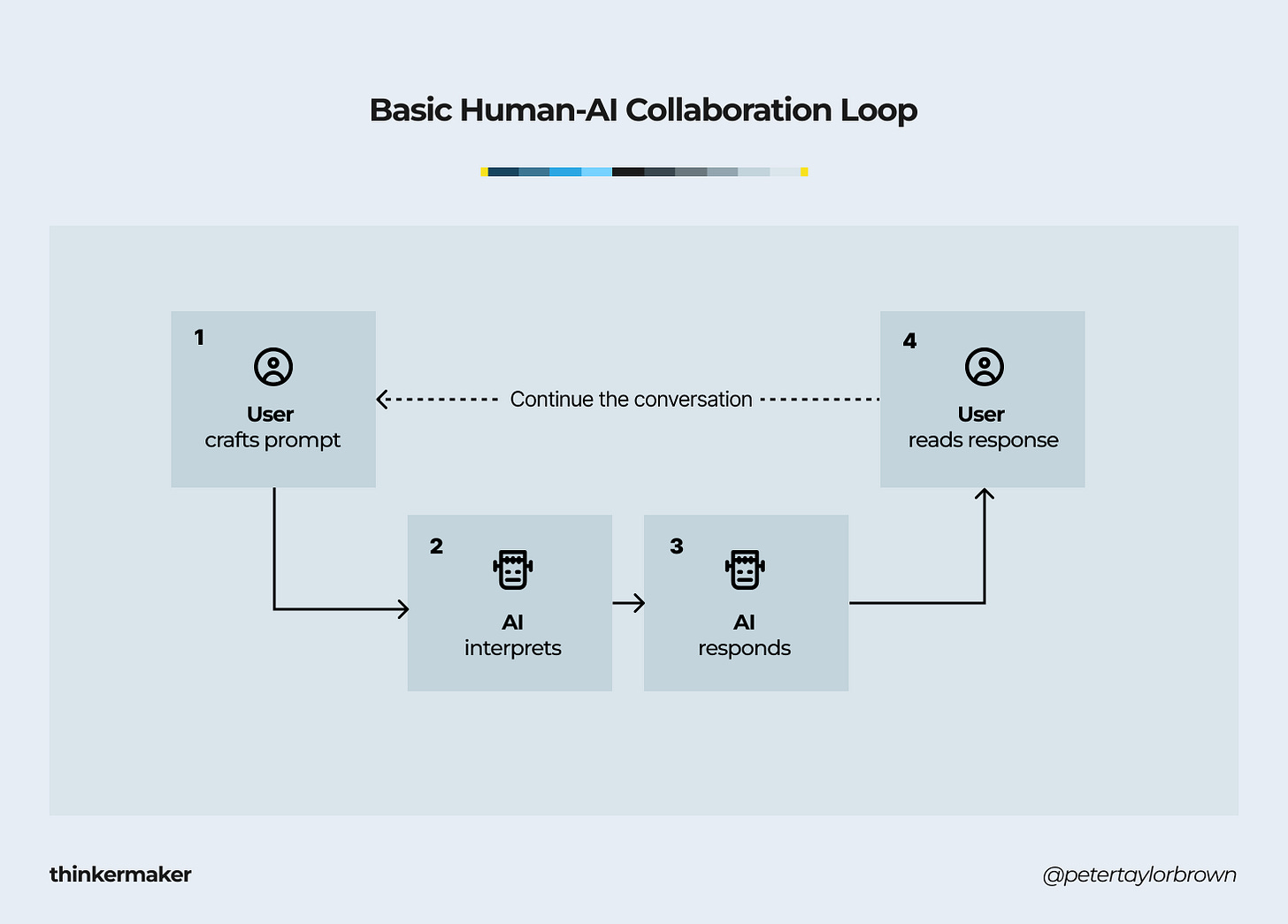

Through a Human Computer Interaction (HCI) lens, this is the basic workflow:

You say something to it, it “thinks”, it gives you a response, and you review that response. Then you iterate as needed. It should sound a lot like person-to-person communication, because it’s fundamentally identical.

Via prompting, you are guiding the machine’s focus as you collaborate. You are shaping what it pays attention to in-the-moment as you work through something together. It’s a skillset that develops quickly when you build from a few foundational perspectives and approaches.

How to get better at prompt engineering over time

Take a pragmatic approach

As with improving how you collaborate with people, and frankly anything where experimentation won’t cause irreversible catastrophe, the best way to up your prompting prowess is by simply doing it and staying curious. You will gradually learn how to iterate and structure prompts in ways that works well for your needs as you gain more comfort with the new medium.

It can be a fun, albeit sometimes frustrating learning process with lots of trial and error. Just be forewarned, you are working with a machine that, without thinking, has ingested more information than you can imagine and has been frequently described as deeply sycophantic for a long time (Tech Crunch / The Atlantic / Nielsen Norman / Open AI). On top of that, it has poor basic judgement, tends to hallucinate, and frequently loses context.

I think about it like working with a colleague who is gleefully well-read but not at all experienced, and terrible at filling in the blanks. You are the facilitator. Your collaborator is a golden retriever.

The quality of response is extremely dependent on the clarity of information, structure, and guidance of your prompts. Yes, we now have more context-setting tools available, but it still behooves you to consider and learn ways of better defining what you are doing and want to get back. And to your benefit, many of these skills are not new. They simply need to be honed for talking to a machine.

The pragmatic approach? Be patient, literal, and generally sequential, building up gradually then looping back when you sense a drift. And make sure you are leaning on the skills you already have.

Spoiler Alert: You were building the skillset before AI arrived

There’s a lot of discussion right now about building the skills to talk to machines, with a growing acknowledgement that many skills are more fundamental, even independent of AI. Prompting skills are only part of great prompting.

Much of your effectiveness comes from lifelong skillsets built through years of learning and experience both generally and in your field. As an example, it’s a fundamental principle that your questions and assertions are as interpretable as your clarity in thinking and articulation, which also need to be matched to the abilities of the other party. It’s no different here, except in this case the “other party” is simply a machine.

The human layer will always be your ability to work through a specific topic or problem area while structuring information and communicating intentions both in the moment and over time. Output quality comes from the artful combination of asking questions, establishing mutual understanding, and guiding an outcome-driven conversation from beginning to end.

If your questions and guidance are non-specific, unclear, use imprecise language, or rely on assumptions kept in your head, progress will reflect that.

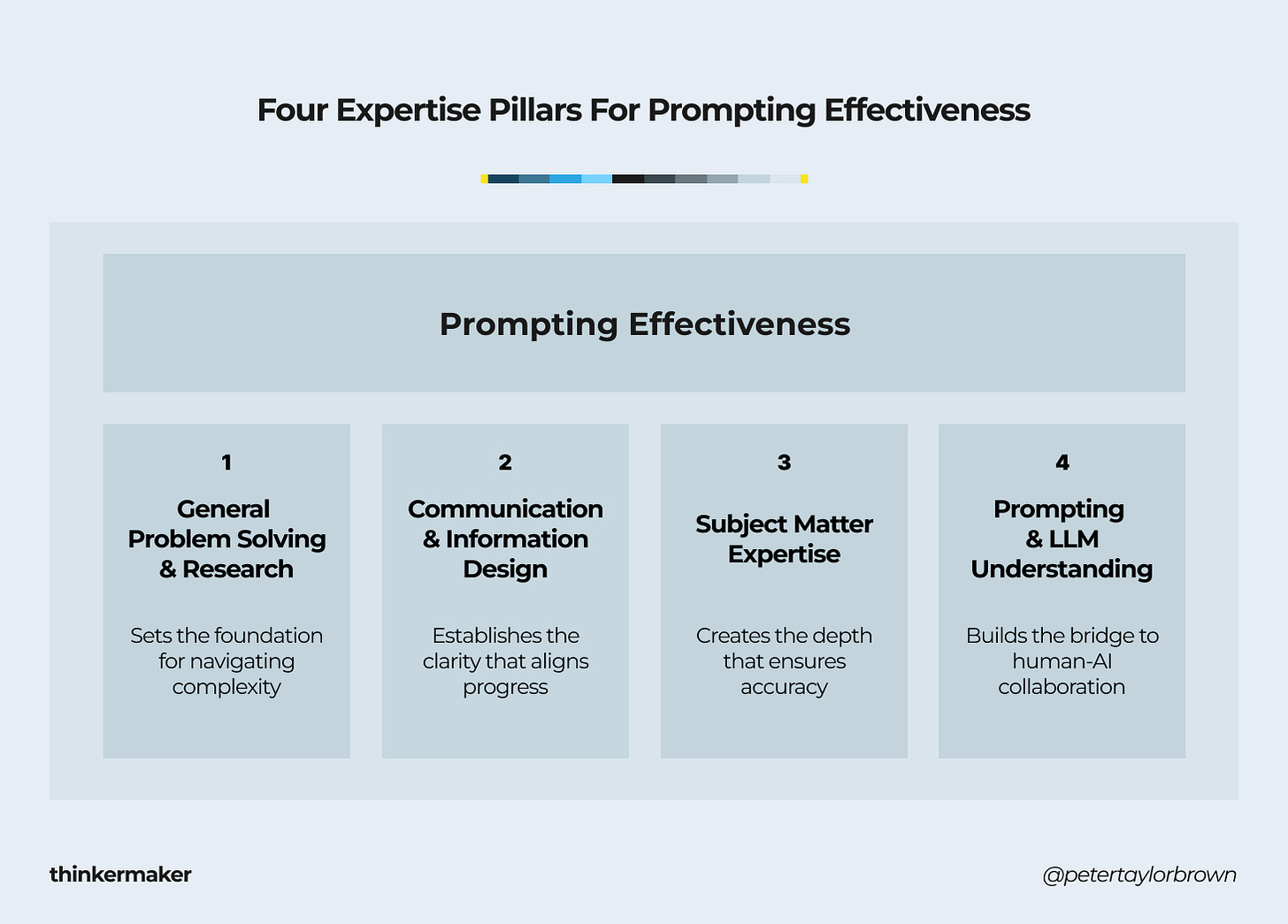

With that, I want to propose four foundational areas of expertise that support your prompting effectiveness. Since three of the four have nothing to do with AI, this should feel a bit more tangible and accessible, helping you connect your prompting skillset to what you already know.

Four expertise pillars for prompting effectiveness

1. General problem solving & research

Sets the foundation for navigating complexity

Problem solving and research skillsets will determine how well you get into a topic space, define existing problems, break problems down into component parts, and tackle those parts in the order the situation needs. There are a ton of frameworks in this area, with some more specialized. The more you know and are comfortable using, the more intuitive and intentional you can be in your approaches.

2. Communication & information design

Establishes the clarity that aligns progress

The way you phrase and order information, both during sequenced execution and in synthesis for reuse, has massive implications for how well you move forward. Think of how you might communicate and guide people during collaborative sessions, to how you create structure around ongoing bodies of work. It should be easy to follow along, to subdivide, and to pick up where you left off. The prompt is simply your in-the-moment thread as you guide and shape progress.

3. Subject matter expertise

Creates the depth that ensures accuracy

It’s generally a great idea to have experts in or accessible to teams. You can better work from what is known and not known, employ best practices contextually, know the right questions to ask, and the right language to use. This all helps you move forward with more accuracy and precision. The counterpoint — many breakthroughs come from master generalists bringing insights laterally into new fields, especially as it helps ask the “dumb” questions that can lead to fundamental changes in a field. The key here is balance. Be humble and get informed, applying your own expertise while diligently verifying information outside it with reliable sources. Do your best to get to the right depth for the need at hand.

4. Prompting and LLM understanding

Builds the bridge to human-machine collaboration

This is the “understanding the other party and how to work with them” part of collaboration. At a basic level, how does who or what you are talking to think and respond? What might that mean for how you collaborate? We explored some useful conceptual undertanding of LLMs in Part 1 if you want to circle back, and are discussing more prompt-specific skillsets here in Part 2. The field of expertise around talking to machines will keep growing — we are very early.

If you think I missed something or have thoughts to add, I’d love to hear your perspective. I’m deliberately putting this thinking out here early and it may turn into another dedicated post or a useful framework for the community. For now, please critique :)

Let’s move into skill-building within area #4.

Skill-building in prompting

With more mechanisms becoming available to frame the conversation outside the prompt, we've moved a long way from the days when prompting was the only way to create conversational context. Even so, prompting is still the primary lever for talking to machines.

You can still get pretty far only using the prompt, moving to context engineering only when you begin feeling limited. Any context you have can still be communicated up front to prime conversations using prompting best practices.

Structures and approaches have been tested and refined to take advantage of the “thinking” process and biases of LLMs, raising the quality of responses. General tricks can work in most situations, as well as task-specific ones such as for market analyses, branding exercises, and all kinds of research. There’s no need for you to reinvent the wheel or struggle to get quality responses up front.

By using proven approaches to help structure the “thinking” of the machine, it will do a better job of following along and supporting your thinking. Try out tricks around how to add context within the prompt as instructions or background information, topical or stylistic language to increase specificity, examples of output structures to best suit your needs, and even ways of forcing it to verify information. From there, you can iterate and learn.

You will inevitably find the edges as you experiment, discovering interesting behaviors that spark new questions for you. Many of these questions will have already been explored by the engaged builder community.

As an example from my own workflow — I was facing issues in my own product research with responses that included ADHD and attention science claims I knew were outdated and off-base. Thankfully, a serendipitously shared method that leverages the power of role-based prompting techniques in a slightly different way appeared in my feed.

After testing it out and seeing a drastic accuracy difference, it’s become a go-to for me over the past few weeks:

Type your normal prompt & context

Append a role-play request to either A: review and analyze the first answer or B: do the same task again, as a subject matter expert you specify (e.g., market analysis expert, branding expert, ADHD science expert, etc.)

Ask it to merge the results into a single response

Press enter, and voila! Built-in iteration with “expert” review.

The extra steps introduce intentional bias, forcing the LLM to look at its own response through a new lens, finding any issues or areas to polish. It’s especially effective multiple times in one chat as you iterate with your robot helpers.

And that’s just one trick of many, all of which become even more powerful when you know how to navigate the flow of conversation.

Chunking and re-anchoring your conversation

People have already discovered through trial and error that larger, more detailed up-front prompts do not always create better results. Diminishing and sometimes reverse returns can be observed from adding too much context, referred to now in the AI community as “context rot”. We’ll get into that topic further in Part 3.

For now, know that prompt design isn’t just about jamming more into a prompt. It’s about understanding and sensing how much the model is meaningfully keeping track of, so you can build on an idea or thread of conversation more effectively.

And if you relate it to team work, it’s not all that different. Unless you are insanely masochistic, you would never go into a meeting and say “here are all the things we need to solve… go!” It would be utter chaos. You’d have competing conversations, crossed-logic, different levels of abstraction, and some looking at the forest while others looked at the trees.

Even as context windows, i.e., the machine’s “short-term memory” discussed in Part 1, get larger, drop-offs in quality or drifts in attention over the length of a conversation happen regularly. It’s as if the short term memory is getting overloaded in the machine. The LLM can get confused (though of course being sycophantic), contradict itself, and seemingly lose the flow of conversation. You will just need to feel this out and pay attention.

Right now, there are various approaches that tend to help based on how we already work in teams.

Here are two of them:

Chunking: Break down the problem or task into component parts, building on an answer sequentially and iteratively. With this approach you can keep better focus while having continuously improving references during thinking and solution development. Maybe even as external documents and notes.

Re-anchoring: The thread will get lost, due to the LLM or intentionally as you explore various paths. When you drift off course, take advantage of those references from 1 to the conversation back to a point of solid ground. Or start a new chat using those references to start a bit more fresh.

Both of these are classic facilitation and team management skills, just applied to talking with machines. I imagine it like this — you have an idea that you are gradually shaping with the AI (your team). You have an intent up front of what you want to solve for or unpack.

Depending on complexity, it may take investigation, iteration, stumbling forward, getting off track, and coming back to the intent. Over and over. It’s all part of problem solving together.

Over time, as context can be more intentionally shaped and managed outside the prompt, with response issues getting improved on over time, we will see changes in how we prompt.

A prediction: How prompting will continue to evolve

In the early days, the prompt was the only way for a user to enter anything. It was all of the context, resulting in bulky prompts that were fairly over-engineered.

Over time, there has been a clearer separation of roles. Prompts now serve more to guide intent in the moment, while context can be increasingly set outside the prompt to shape approaches across conversations. That separation has already made collaboration more reliable, by allowing intentions to be more deliberately systematized across conversations.

Context engineering will continue expanding into a richer set of tools. New product features will let things like information, user preferences, and process instructions live outside of the prompt. Context drift in the underlying models will likely reduce as context windows expand and memory tools improve, but it may not vanish entirely.

As this happens, prompt engineering will likely narrow and deepen as a sub-practice, with more consistent ways of talking to the machine being established. Prompting will have room to become more conversational and natural, evolving into a conversational layer on top of structured context systems.

For example, rather than cramming processes into a long prompt, you’ll reference them — go through X process, run it against Y data. We already think this as part of specialized roles, there is just a barrier to action. Those workflows have always needed heavy engineering before they can be done. Increasingly, workflows may only need to be described at a high level, with the more context tools made available to the AI.

If you have any thoughts on this future, or really anything from this post, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. It’s been a pleasure writing this and sharing it with you.

If you want some rabbit holes, especially if you are interested in understanding the mechanics under the hood, here are a few good ones:

Prompting 101 | Code w/ Claude (25 min): Great presentation video from Anthropic starting in but going beyond prompting basics.

Prompt engineering overview - Anthropic: A developer guide for prompts with Claude models.

Prompting - OpenAI API: Learn how to create, optimize, save, and reuse prompts with OpenAI models.

OpenAI Cookbook: Open-source examples and guides for building with the OpenAI API. Browse a collection of snippets, advanced techniques and walkthroughs. Share your own examples and guides.

This Talking to Machines post is the second of a three-part series. If you found this insightful or interesting, hitting the like button helps me know it resonated. And if you want to follow along, or help this thinking reach more people, please follow or subscribe.

Here is the last post in the series:

Talking to Machines, Part 3: Designing the AI’s world with context engineering

Keep thinking and making. And be well.

Have a wonderful day.

- Peter

Read Part 3 next:

Talking to Machines, Part 3: Designing the AI’s World with Context Engineering

Talking to Machines is a three-part series exploring the rich changes in interacting with AI and what that means for improving how we work with it.

Thank you @Karen Spinner for the restack! Really appreciate you doing that 🙏🏻

You articulated this really well: The people who collaborate most effectively with AI are not necessarily the most technically sophisticated. They are the ones who already knew how to think and explain themselves clearly. (Btw, your "golden retriever" analogy is perfect!)

Your post made me also think how this connects to the parenting conversation happening right now around AI. Parents are being asked to help children use AI as a thinking aid rather than a thinking replacement, but your article reveals a challenge. Effective AI use requires skills that take years to develop. We are perhaps asking children to be good "AI managers" before they have developed the underlying cognitive muscles (problem decomposition, clear articulation, iterative thinking) that make someone good at it.